Here are ten incredible features of the Avro Vulcan bomber:

10: Remarkable Timing

The Avro Vulcan bomber emerged at a pivotal moment in aviation history and global politics. It’s often highlighted that a mere decade separated the introduction of the angular Avro Lancaster bomber to the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1942 and the Vulcan's maiden flight on 30 August 1952. This ten-year leap represented an astonishing technological advancement. During this period, Avro transitioned from producing bombers capable of around 282 mph to aircraft that could achieve a staggering 646 mph.

This rapid progress wasn't just about speed; it was about foresight and strategic necessity. As aviation designer Sir Sydney Camm once observed about another aircraft, "All modern aircraft have four dimensions: span, length, height, and politics. [It] simply got the first three right." Camm's observation, while insightful, missed another crucial dimension: time. The Avro Vulcan not only mastered these dimensions but also benefited from exceptionally opportune timing.

Its arrival as part of Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent force in the late 1950s, preceding the Handley Page Victor by two years, placed it at a critical juncture in the Cold War. Furthermore, the Vulcan was fortunate to enter service before the impactful 1957 Defence White Paper, which controversially declared manned military aircraft largely obsolete. This paper significantly curtailed development on later projects, such as the Mach 3-capable Avro 730 bomber and reconnaissance aircraft.

9: The Blue Steel Missile

While the Vulcan possessed impressive performance capabilities, the RAF recognised its potential vulnerability to the evolving landscape of Soviet surface-to-air missiles and advanced air defence fighters. Direct assaults on heavily defended targets posed a significant risk. Consequently, the need arose for a ‘stand-off’ weapon, one that could be launched from a safer distance from the target.

Avro, the manufacturer of the Vulcan, addressed this requirement by developing the Blue Steel missile. This project was part of the "Rainbow Code" series of British military initiatives, which included the rather creatively named Indigo Corkscrew.

Blue Steel was a substantial, rocket-propelled, nuclear-armed missile designed to be launched from beneath the Vulcan. Measuring an impressive 10.7 metres (35 feet) in length and weighing over three tons, it carried the formidable "Red Snow" thermonuclear warhead. This warhead possessed a destructive capability equivalent to over one million tons of TNT. The missile was capable of reaching hypersonic speeds, up to Mach 3. However, Blue Steel's operational lifespan was relatively short, just seven years. During this period, it proved to be unreliable and cumbersome to prepare for launch. It was ultimately retired on 31 December 1970, as the United Kingdom's strategic nuclear capability transitioned to the Royal Navy’s Polaris submarine fleet.

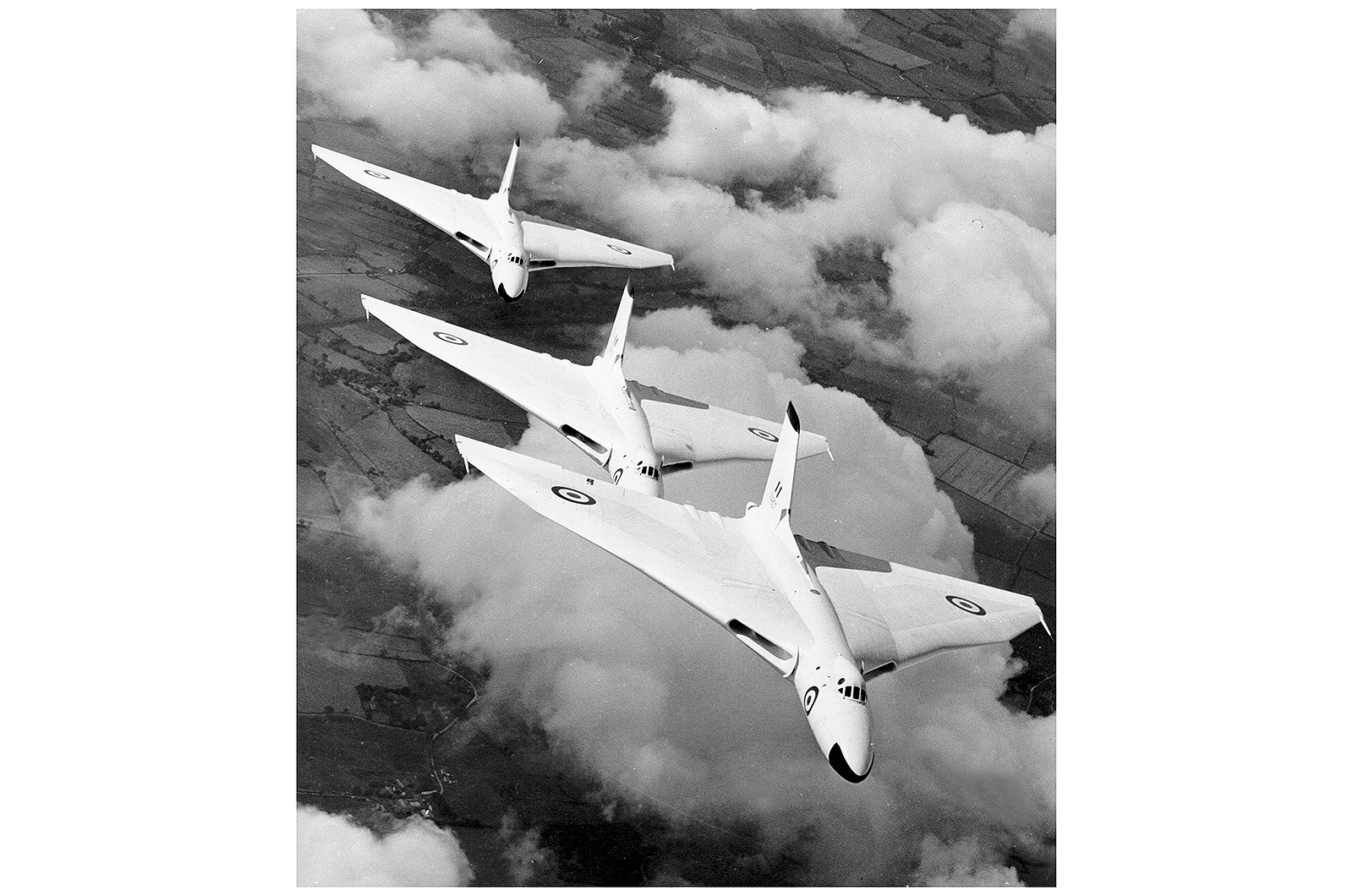

8: Exceptional Performance

A significant contributor to the Vulcan's enduring affection is its remarkable performance, particularly as an airshow exhibit. Its dramatic, cloaked silhouette, coupled with a thunderous, car-alarm-inducing roar and sprightly handling, captivated audiences. Unlike many bombers, which are often perceived as lumbering, the Vulcan exhibited agility more akin to a large fighter aircraft.

The aircraft's low wing loading and a high thrust-to-weight ratio endowed it with astonishing manoeuvrability for its considerable size and mass, especially at high altitudes. At these altitudes, the Vulcan presented a frustratingly elusive target for fighter aircraft attempting interception practice. Its high-altitude performance was truly exceptional, with reports of the aircraft reaching altitudes as high as 60,000 feet (18,288 metres). Furthermore, the Vulcan was faster than its American counterpart, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, and possessed the range to strike targets within the Soviet Union from bases located in Britain.

The Vulcan's substantial wing area and powerful engines also contributed to impressively short runway performance. Unusually for a large aircraft of its era, and indicative of its excellent handling characteristics, it was controlled via a fighter-style stick rather than a conventional large control yoke.

7: The Unforgettable Sound

Anyone fortunate enough to witness a Vulcan in flight, or even to hear its engines being tested on the ground, will attest to its deafening roar. The Vulcan's raucous howl was a beguiling characteristic. But what exactly produced this distinctive and powerful sound?

We consulted with Michael Carley, a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Bath, whose research specialises in aeroacoustics and the numerical modelling of vortex-dominated flows and acoustics. His expertise makes him ideally placed to explain the Vulcan's unique sonic signature.

According to Carley, the Vulcan's engines were loud because they were relatively small. Jet engines generate thrust through the product of mass flow rate and exhaust velocity. For a given thrust requirement, smaller engines necessitate a higher exhaust velocity, and noise levels increase exponentially with jet exhaust speed. This is one reason why modern aircraft often opt for two larger engines rather than four smaller ones, where feasible.

The distinctive "howl" is attributed to acoustic resonance within the air intakes. While this can be loosely compared to the sound produced when blowing over the top of a bottle, a more accurate analogy might be the sound of wind whistling over cavities and around buildings, or the exhaust or intake noise from a high-performance car or motorcycle. At a stretch, it could even be likened to certain musical instruments.

6: Quick Reaction Alert (QRA)

During the 1960s, the Royal Air Force maintained a substantial fleet of Vulcan bombers, presenting a formidable deterrent. Nine frontline squadrons and one training unit were equipped with the type. From 1962, the V-Force operated under a heightened state of readiness known as Quick Reaction Alert (QRA).

This status meant that one bomber from each squadron was designated to be on constant ‘cockpit readiness’ – a number later increased to two. In the event of an attack on the UK or the commencement of nuclear hostilities, the QRA aircraft were tasked with taking to the skies within minutes to execute a counterattack.

The Vulcan arguably excelled among the V-Force bombers in its suitability for Quick Reaction Alert duties. It possessed the capability to start all four of its engines, with flight instruments and flying controls brought online, in just twenty seconds at the touch of a single button.

Former RAF Vulcan navigator Mike Looseley recalled the impressive quick-start capability. He noted that it could initially be initiated by the crew chief from a power set located outside the aircraft. However, following an unfortunate incident involving misplaced aircraft door keys, this procedure became less common.

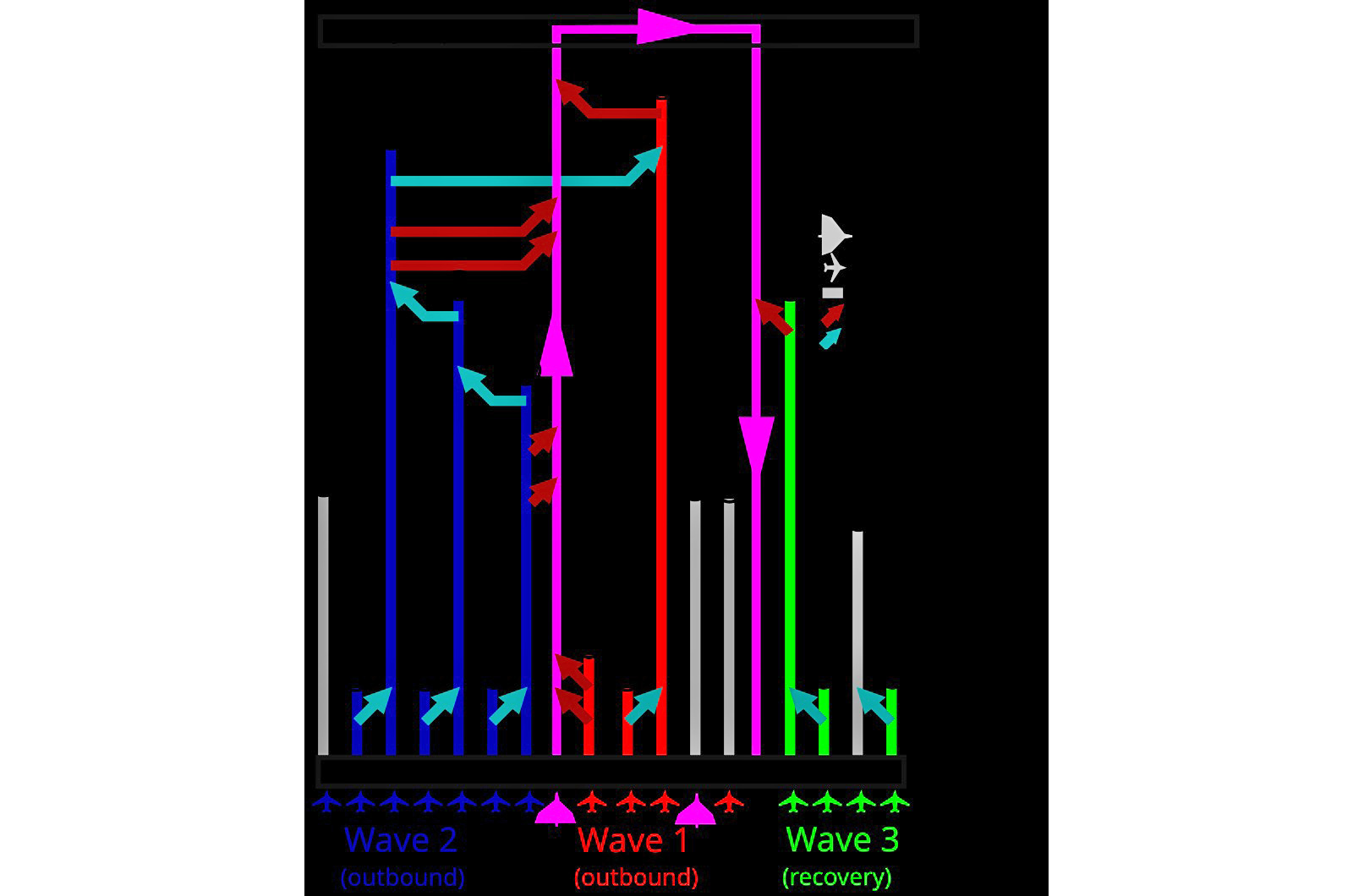

5: Operation Black Buck

In 1982, when RAF Vulcans executed the Operation Black Buck attacks against targets in the Falkland Islands, they undertook the longest-distance bombing raids ever recorded. The objective was to strike Port Stanley airfield and its associated defences, a staggering 7,600 miles (12,200 km) round trip that took 16 hours.

Adding to the immense challenge, the RAF Vulcans were nearing the end of their service lives and were ill-equipped for the demands of modern warfare. Many essential parts were not fitted, and components had to be sourced from any available means, including a museum. Black Buck operations were launched from RAF Ascension Island, a volcanic outpost in the South Atlantic Ocean. The missions demanded an extraordinarily complex air refuelling strategy.

There was no guarantee of success, and the Vulcan had not yet been tested in combat. It would face formidable enemy air defences. Armed with unguided bombs and Shrike anti-radar missiles, the Black Buck missions, despite facing almost catastrophic bad luck, ultimately succeeded in what was, and may remain, the most complex air attack mission ever planned.

Against considerable odds, five of the seven Black Buck missions successfully delivered their attacks. The Black Buck operations remain somewhat controversial, with some questioning the value of the immense effort while others argue that the raids served as a powerful deterrent against further Argentinian military actions.

4: A Versatile Testbed

The Vulcan's significant ground clearance, relatively high top speed, and excellent high-altitude performance made it an ideal platform for testing high-performance jet engines. In this capacity, the Vulcan made substantial contributions to the development of three highly significant aircraft projects: two military and one civil.

One of the most technically demanding aspects of creating the Concorde supersonic airliner was the design of its remarkable engines. In 1966, the Vulcan conducted air-testing of Concorde's Olympus 593 engine. The 593 was an evolution of the engine originally developed for Britain's cancelled supersonic TSR-2 bomber, which had also benefited from engine testbed work carried out by the Vulcan.

The Vulcan also played a crucial role in the development programme of the Panavia Tornado fighter-bomber. The Tornado's Turbo Union RB199 turbofan engine was flight-tested using an Avro Vulcan, with the engine installed in a nacelle that accurately represented the Tornado's configuration. The Vulcan first flew with the RB199 nacelle fitted in 1972.

Furthermore, another key Tornado technology tested on the Avro Vulcan was the Mauser 27mm automatic cannon. This cannon, used on the Panavia Tornado and later on aircraft such as the Dassault/Dornier Alpha Jet, Saab Gripen, and Eurofighter Typhoon, was fitted alongside the RB199 nacelle to assess gun gas ingestion.

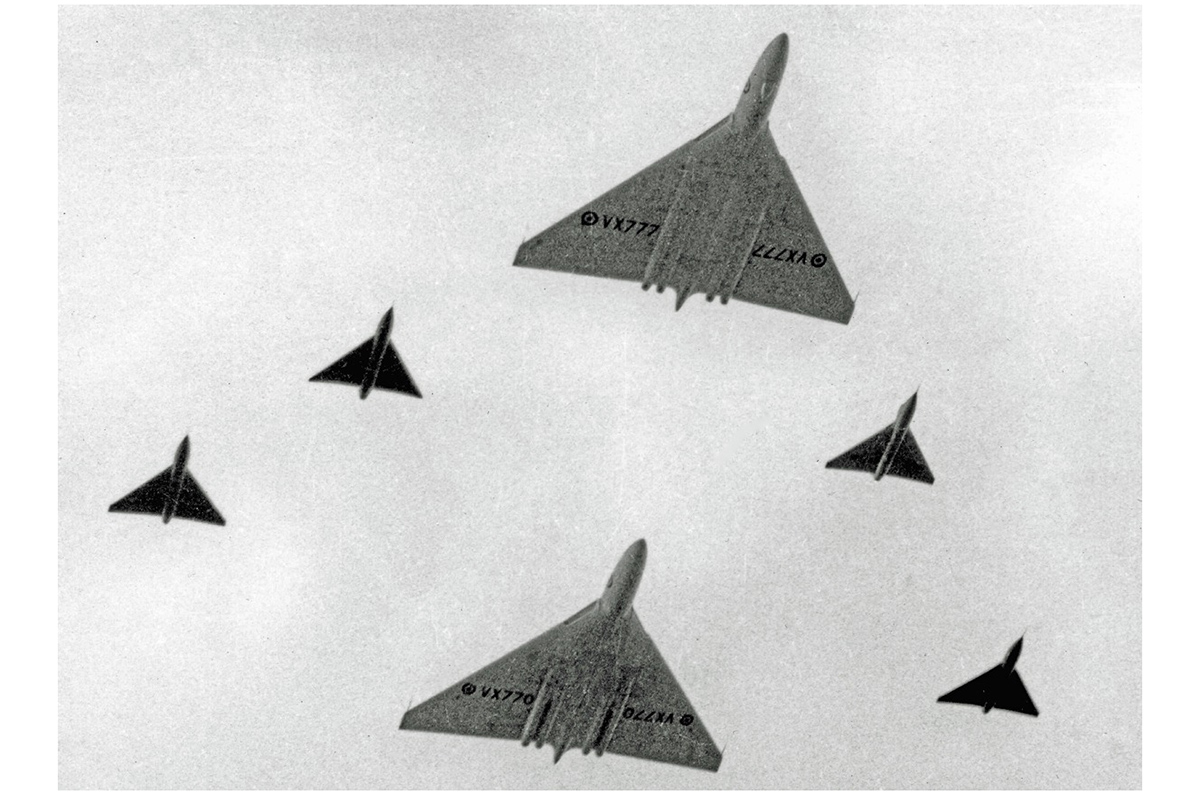

3: The Avro 707 Experimental Aircraft

During the development of the Vulcan, there was limited understanding of the characteristics of delta (triangular) wings. While the delta wing offered potential structural and aerodynamic advantages at higher speeds, significant questions remained regarding its safety and handling at lower speeds. Adding to this complexity, the proposed bomber was designed to be tailless, meaning it lacked a conventional horizontal tailplane.

Tailless aircraft were believed to offer reduced drag and were a fashionable design trend at the time, with many impressed by the speeds achieved by the tailless Messerschmitt Me 163 during World War II.

Tailless aircraft had been flown earlier in the 20th century by aviation pioneer J. W. Dunne. However, the advent of high-speed jets presented a new set of challenges. To thoroughly investigate the flying qualities of the tailless delta configuration for the Vulcan project, Avro constructed the 707 experimental aircraft series.

The 707 was built to a scale of one-third of the Vulcan. The first 707 took to the air on 4 September 1949. Tragically, just 26 days later, the initial prototype crashed near Blackbushe during a test flight, resulting in the death of Squadron Leader Samuel Eric Esler, DFC, AE. A total of five 707 aircraft were built, and they were instrumental in exploring various aspects of tailless delta-wing flight.

2: The Iconic Delta Wing

The Vulcan was among the pioneering delta-winged aircraft to enter operational service, entering service in September 1956. This followed the service entry of two delta-winged fighters: the British Gloster Javelin in February and the US Convair F-102 in April of the same year. Delta wings offer significant structural integrity and provide a large internal volume, which can be utilised for fuel storage or housing engines, as was the case with the Vulcan. The Vulcan's distinctive triangular, or ‘delta’, wing is its most recognisable feature, boasting an impressive area of 3,554 square feet (330.2 m²).

The adoption of a delta wing for an aircraft operating at subsonic speeds, like the Vulcan, was unusual. One of the primary reasons for choosing this design was that it allowed for the necessary structural stiffness using the manufacturing techniques that were readily available at the time. In contrast, the rival Victor bomber's crescent wing necessitated the development of more advanced spot-welded honeycomb structures.

Early versions of the Vulcan featured a straight leading edge on the wing, the part that first encounters the air. This design presented aerodynamic challenges, which were subsequently addressed by introducing a kinked leading edge for the B.1 and B.1A variants. The B.2 model further refined this approach and increased the overall wing area.

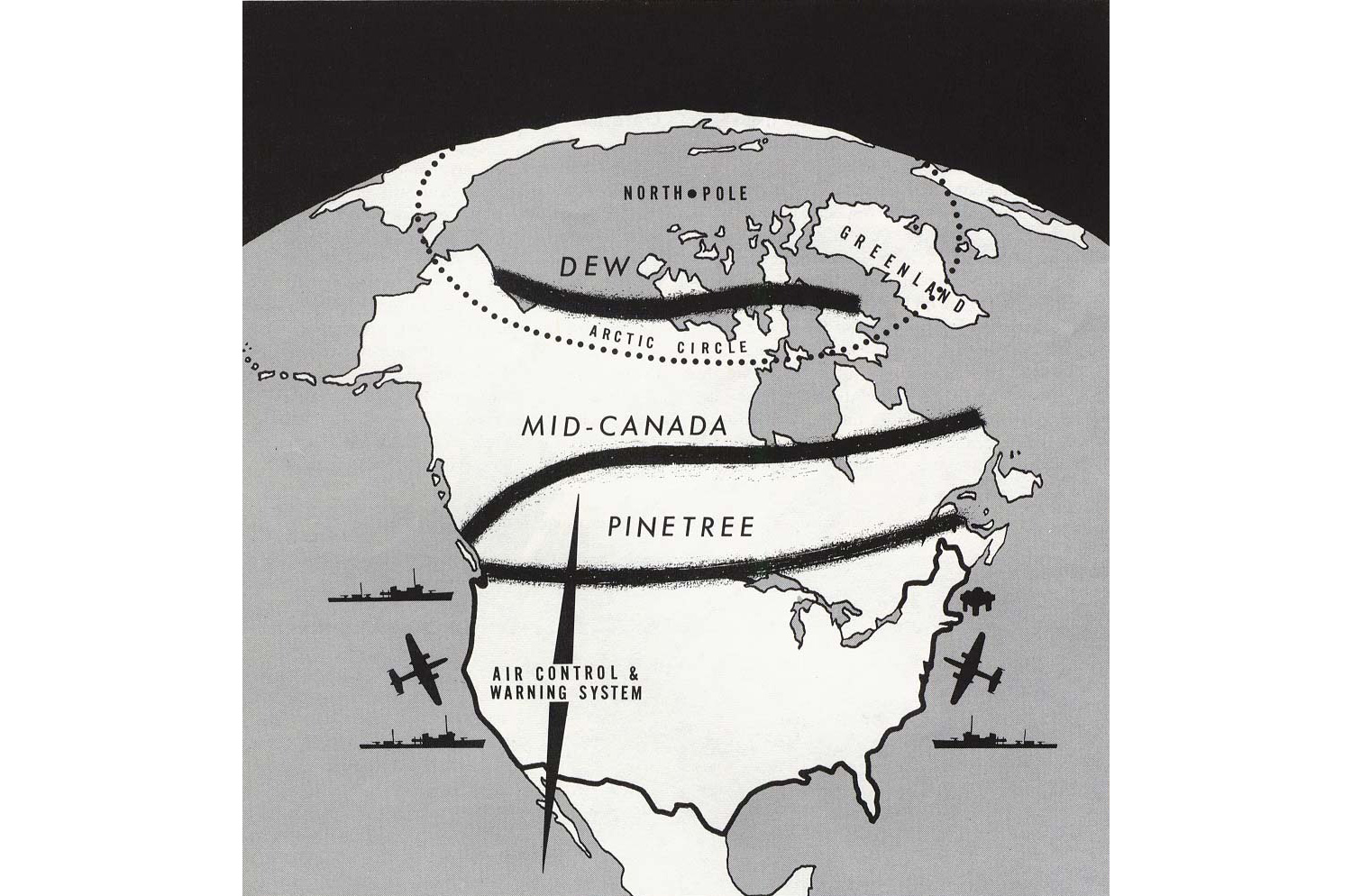

1: Exercise Sky Shield

In the early 1960s, the North American Air Defense (NORAD) Command and Continental Air Defense (CONAD) sought to assess the effectiveness of North America's defences against large-scale aerial attacks. Exercise Sky Shield was conducted to address this critical question, involving a vast training exercise that simulated numerous Soviet bombers.

RAF Avro Vulcan B.2s participated in Sky Shield II in 1961, simulating Soviet heavy bombers operating at extremely high altitudes of 56,000 feet (17,000 metres). Simultaneously, B-52s attacked at altitudes between 35,000–42,000 feet (11,000–13,000 metres), alongside lower-flying B-47 Stratojets.

The Vulcans combined their high-altitude operations with highly effective electronic jamming techniques to evade successful detection. A 27 Squadron Vulcan, operating from Bermuda, managed to evade the defending USAF F-102 Delta Dagger interceptors and effortlessly landed at Plattsburgh Air Force Base, New York. A northern contingent of four Vulcans also performed admirably, with all their aircraft successfully landing in Newfoundland.

Remarkably, not a single Vulcan was deemed 'lost' to the defending forces, and there was minimal success in detecting the Vulcans. Sky Shield II represented a significant triumph for the Vulcan force and served as a stark wake-up call for NORAD. It wasn't until 1997 that most of the results from Sky Shield II were declassified, revealing that no more than a quarter of the simulated bombers would have been intercepted, and none of the Vulcans.

The Vulcan was retired from RAF service in 1984. One aircraft, XH558, continued to be operated for display purposes until 1993. It was subsequently restored by a civilian team, which operated it at air displays between 2008 and 2015. It is now preserved at Doncaster Sheffield Airport.

No comments:

Post a Comment