Media outlets are grappling with an increasing issue: their websites and logos are being replicated to disseminate misinformation. Here’s what’s driving this trend—and how you can identify the impostors.

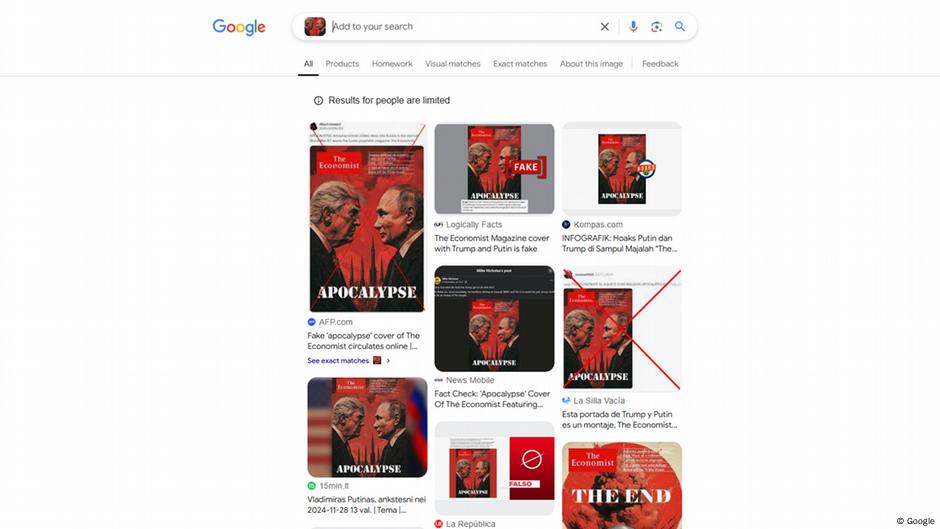

Shortly after Donald Trump secured his second term as US President in November, an image of the front cover of The Economist magazine began circulating online with captions in multiple languages.

It said "Apocalypse" and depicted Donald Trump confronting Russian President Vladimir Putin against a backdrop of several intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Several remarks associated with the cover expressed concerns over the potential onset of World War III and pondered the possibility of nuclear weapon deployment.

Nonetheless, this front cover was never actually created, and The Economist did not run such an article. Additionally, the supposed cover is absent from the publication's archives.

This deceptive strategy is referred to as 'media spoofing.' An increasing number of well-respected media organizations globally have had their logos, websites, social media accounts, and overall appearance exploited to disseminate inaccurate or deceitful information.

This tactic of spreading misinformation isn't novel, yet it appears to be escalating across various parts of the globe, evident from the extensive array of contemporary instances.

An example of this is the screenshot of a fake CNN story claiming that Elon Musk’s satellite network, Starlink, was responsible for causing blackouts in Ukraine following President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's controversial meeting at the White House.

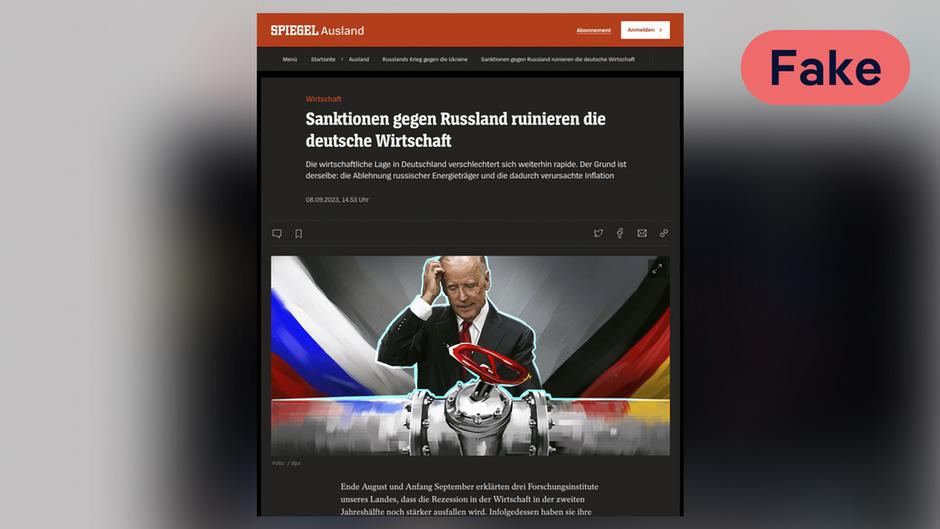

Or this replicated version of the German magazine Der Spiegel featuring the title "Sanctions Against Russia Are Damaging Germany’s Economy."

Or this website, resembling that of French daily Le Parisien, saying illegal migrants were a threat to the Paris Olympics.

Additionally, there was another tale featuring the E! News logo, suggesting that USAID funded famous personalities' visits to Ukraine. However, INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL's fact-checking discredited this assertion. here This post was shared again by X-owner Elon Musk (with 220 million followers) and by Donald Trump Jr., who has 14.7 million followers on the platform and is the son of the U.S. President.

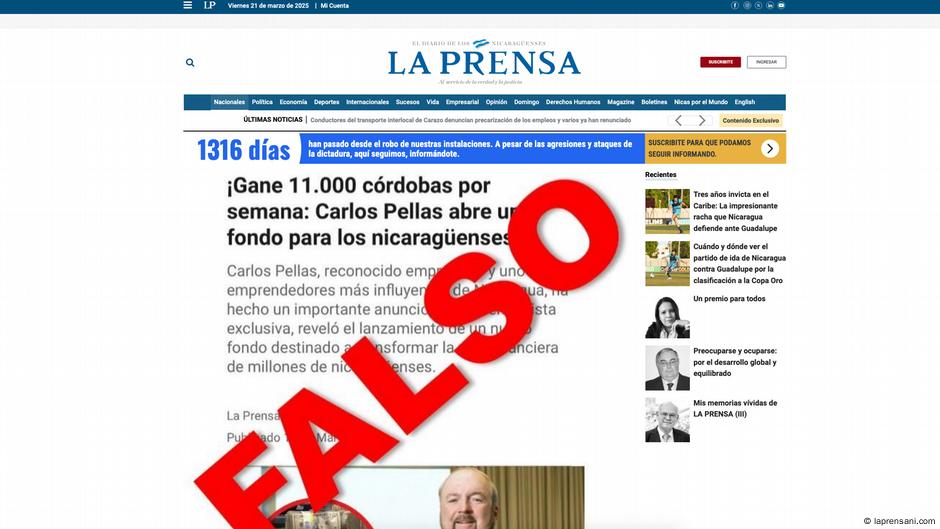

This issue is not limited to the United States and Europe alone. Media organizations across the globe, including Israel’s Haaretz and Nicaragua’s La Prensa, have had their identities stolen.

Moreover, scholars in Nigeria examined multiple fake social media accounts, particularly on Facebook, associated with two English-language newspapers: Vanguard and Daily Trust.

What exactly causes this issue of misinformation, and what effects does it produce?

Most crucially, what steps should you take to ascertain if the news you’re reading originates from a genuine source? For this purpose, INSPIRATIONS DIGITALFact check offers some useful advice.

From basic photo editing to advanced media forgery

These instances illustrate how fake news stories can manifest in various ways: ranging from simple images that have been altered to misrepresent information or incorporate a media emblem, all the way up to full-fledged websites or social media accounts impersonating reputable journalistic entities—referred to as 'spoofed' media sites.

A number of these counterfeit stories utilize artificial intelligence technologies. Typically, they disseminate more rapidly during significant news occurrences such as elections, conflicts, natural calamities, or financial downturns.

As reported by Newsguard, an American organization monitoring misinformation and media practices, 40 credible news outlets have fallen victim to such impersonation scams since 2018. This issue appears to be growing more common over time.

Many of the cases identified by the monitoring group are associated with Russian influence campaigns that promote anti-Ukrainian andanti-Western stories.

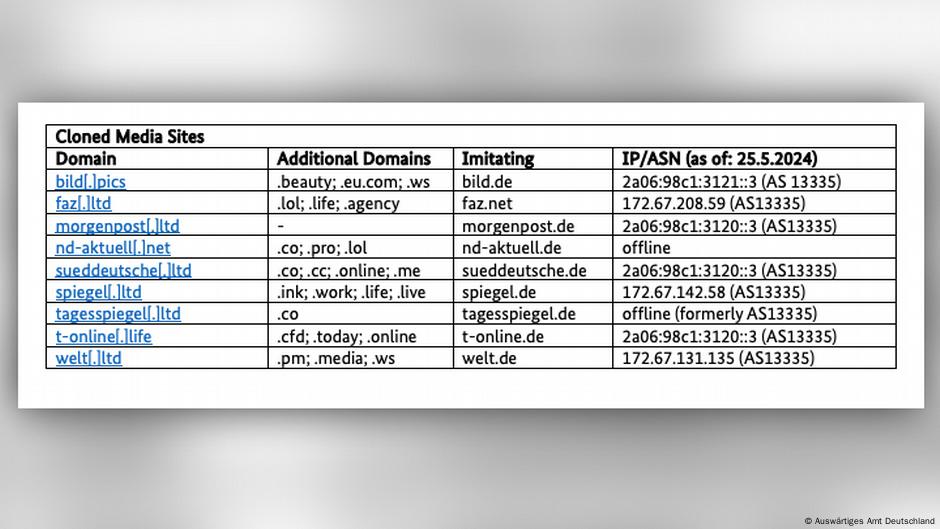

An operation known as the "Doppelgänger campaign" commenced following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Germany , the foreign ministry published a technical report last June detailing how the country was affected by this Russian operation. It includes "dozens of forged clones of mainstream media websites."

McKenzie Sadeghi, the author behind Newsguard's assessment, informed INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL about the typical sequence observed in such misinformation campaigns: assertions made collectively by lesser-known profiles primarily on platforms including Telegram. These statements occasionally get traction when more prominent personalities either intentionally or unintentionally share them.

She stated that the false information keeps spreading until it reaches Russian state media, which attributes the claims to prominent individuals sharing them on social media instead of mentioning the initial Telegram source, thus entirely concealing its true origin.

Diminishing the standards of digital news reporting

Newsguard reports that media organizations most impacted by impostors include the BBC, CNN, Al Jazeera, the investigative journalism entity Bellingcat, Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today.

INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL has likewise become a focus of attention in recent times.

Newsguard reports that media organizations most impacted by impostors include the BBC, CNN, Al Jazeera, the investigative journalism entity Bellingcat, Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today.

INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL has likewise become a focus of attention in recent times.

However, the patterns, subjects, and key players aren't consistent across the board due to distinct regional differences.

In Nigeria, counterfeit versions of newspapers such as Vanguard and Daily Trust have circulated false information regarding subjects like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Boko Haram insurgency, or fluctuations in oil prices. These matters have been significant in the country’s domestic discussions.

"Clone media websites pose a significant issue as they have the potential to erode the reliability and caliber of digital journalism, influence public perception, disrupt the democratic process, and weaken societal unity," stated Abubakar Tijjani Ibrahim, who co-authored the research and teaches at Kano State Polytechnic in Nigeria, during an interview with INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL.

He further noted that because cloned media sites do not adhere to professional ethical standards and safety measures, "those managing these pages often resort to sensationalism, portraying issues in the most inflammatory manner possible."

What steps can you take to confirm the accuracy of the information?

Verify the credibility of a piece of information by integrating thorough examination and scrutiny along with utilizing tools that offer useful (yet not absolute) clues.

The initial recommendation is to check for misspellings or grammatical errors, along with irregular spacing or fuzzy text.

If you're uncertain, consider opening another browser window, navigating to a search engine, and actively searching for the authentic news site. Compare the appearance and design of both pages. Is anything inconsistent or off-putting?

When you visit the actual website, you can perform a keyword search for the claimed piece of information to verify if it exists there. Additionally, you should look into other news sources. Verifying across multiple platforms is crucial. If anything feels questionable, there’s a good chance the story might be fabricated.

If you encounter a screenshot, you can perform a reverse image search using tools like Google Images or TinEye. This might help determine if it has been used previously and if the story has already undergone scrutiny through fact-checking and debunking efforts.

A reverse image search of the Economist’s “Apocalypse” cover uncovered various fact-checks that refuted its legitimacy.

Concerning cloned social media accounts for media organizations, Ibrahim recommended verifying if these profiles include links to the official news outlet’s contact information. Among the ones he examined on Facebook, one clone provided only a Gmail address for communication.

When dealing with cloned news sites, an additional warning sign lies within their URLs or web addresses. Typically, conducting a Google search should lead you to the legitimate website’s address. Upon examining the cloned site, discrepancies might become apparent.

Remember the fake Le Parisien website we mentioned above? There, the URL ended in '.top', while the official URL ends in '.fr.' The same happened with the Der Spiegel webpage: the official site is www.spiegel.de the imitation one was www.spiegel.ltd .

McKenzie Sadeghi from Newsguard suggested that another approach would be to examine the domain registration details, which can be found on platforms like GoDaddy or using Who.is.

She mentioned that there was a counterfeit article on Spiegel.ltd. The domain registration details, which are publicly accessible, revealed that the site was anonymously registered in June 2022, whereas the legitimate website’s domain had been registered much earlier.

In conclusion, stay alert and verify if a narrative originates from a trustworthy news outlet.

This piece is part of the INSPIRATIONS DIGITAL Fact Check series focused on digital literacy. Additional articles within this series encompass:

What signs should I look for to identify edited photos? What signs should I look for to identify images created by artificial intelligence? What signs should I look for to identify audio deepfakes? What signs should I look for to identify government-supported propaganda? What are some ways to identify counterfeit social media profiles, automated accounts, and online troublemakers?And for further information, you can read this link [-]: how INSPIRATIONS DIGITALfact-checks fake news.

Edited by: Rachel Baig

Author: Thomas Sparrow

No comments:

Post a Comment